Empowerment

So far in our little journey into studying this myth, we've only looked at some of the remaining classical sources and some fairly obscure works from the 1800's. Let's briefly depart from that to look at one of the most well-known, culturally pervasive works of art pertaining to this myth: Gian Lorenzo Bernini's 1622 sculpture, Ratto di Proserpina (The Rape of Proserpina).

Even if you aren't that into art and art history, it's pretty likely you've seen it. In recent years, it's frequently been reposted on Tumblr and other sites, particularly as a detail like I've shown above with a particular focus on how realistic Hades' hand looks gripping Persephone's thigh or otherwise showing off Persephone's figure, conveniently cropping out her anguished expression and the tears in her eyes. These reposts also often have people talking about how sexy it is or otherwise romanticizing it.

One post criticizes how others take the work out of context, but they've received responses saying things like "art is in the eye of the beholder" and can have many different meanings, etc. So, let's talk about it: what does this sculpture mean? What is it meant to communicate to the audience? Before we can answer, there's one more thing to note: there was originally an inscription at the bottom that has since been destroyed which read:

"Oh you who are bending down to gather flowers,

behold as I am abducted to the home of the cruel Dis."

This is apparently a message from the titular Prosperina (Persephone), addressed to any young women who might be viewing, warning them to… not look at flowers? or else they will suffer the same fate as her? But, as we have previously discussed, this (being abducted by her new 'husband,' who she has likely never even met before) was the fate of all young women – they had no other choice and no rights. It's like the famous quote from John Berger's Ways of Seeing:

You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting “Vanity,” thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.

Proserpina is simultaneously blamed for getting herself into this horrible situation, while her rape / abduction is sexualized. If anything, it seems that the reactions that you see on Tumblr with this piece grouped thoughtlessly into compilations of various sexy sculptures, paintings, poems, song lyrics, etc, is what Bernini was going for here – it's meant to be a voyeuristic piece. Here, Proserpina is not someone who the viewer is supposed to sympathize with and hope to save, but rather an object to fantasize about.

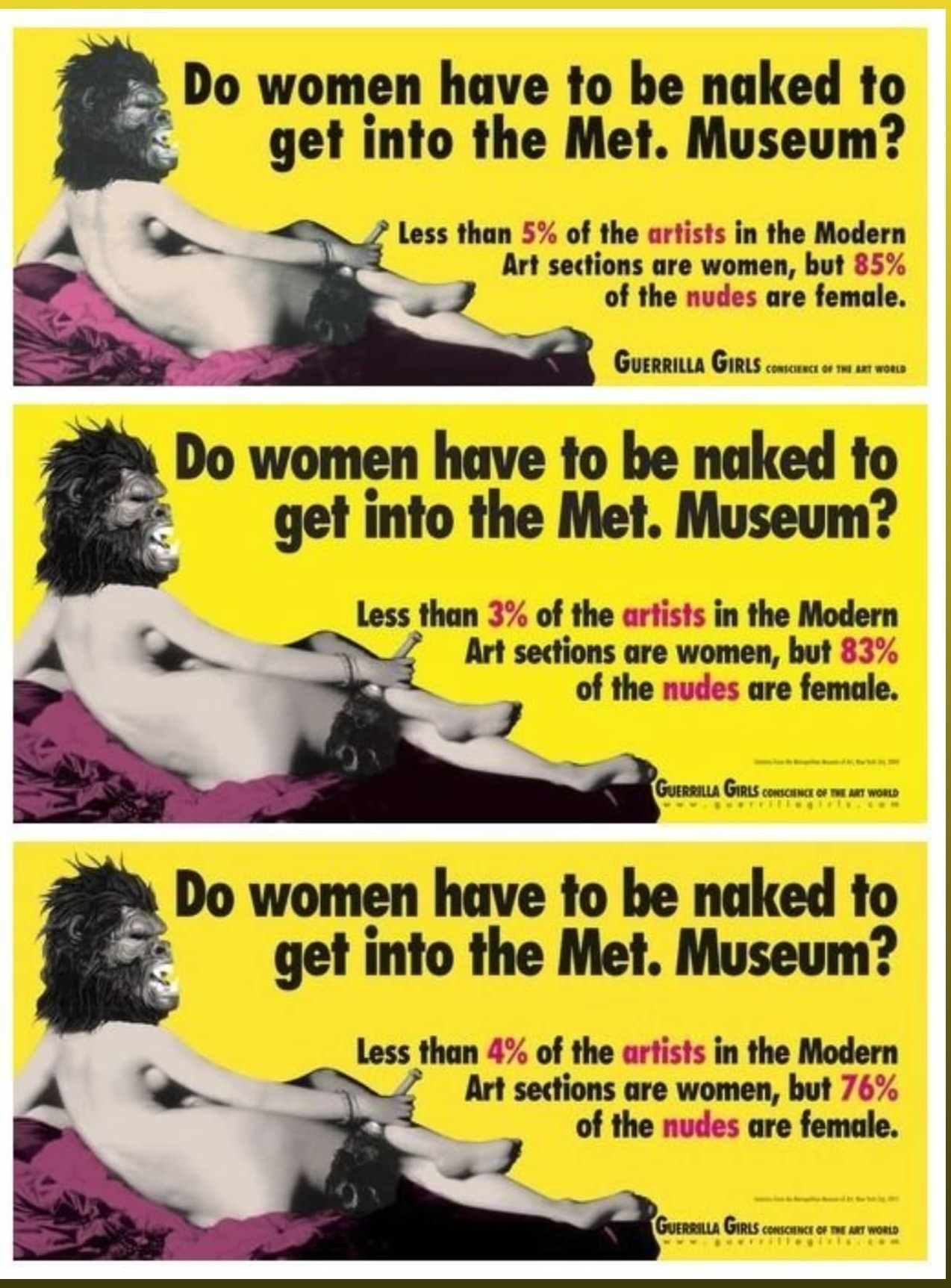

The fetishization and dehumanization of women in art is a common issue brought up by feminists. For example, one long-running ad campaign from the Guerrilla Girls, a feminist group, criticizes the disparity between the large ratio of female nudes and small ratio of female artists featured in the Metropolitan Museum:

Again, we must ask ourselves: what does this say about our culture and how it views women? How does it affect how women and young girls see themselves when they're only shown as the victims of horrific crimes or, worse, their abuse being romanticized? When all they're exposed to is depictions of women created by men for the pleasure of men?

While feminists in the 1970's and 80's certainly did make progress on many fronts, fighting the Hydra of systemic sexism can take a lot out of you! According to Cynthia Eller, in her 1995 book, Living in the Lap of the Goddess, many ended up burnt out from years of political activism that seemed to not get big enough results – they felt that society wasn't listening to them, that they had no ability to bring real change to the world. We still see this feeling of defeatism in modern feminist circles, unfortunately, with sentiments like Fiona Apple's infamous quote “no hope for women" coming up frequently. And so, some of these disillusioned women moved to feminist spirituality to gain a sense of meaning and, most importantly, power that they were missing from the rest of their lives (Eller 211). For example, here's how Charlene Spretnak describes the appeal and importance of Goddess worship in the introduction of the 1992 rerelease of Lost Goddesses of Early Greece:

A woman raised in a patriarchal culture is told that she has the wrong type of body-mind to be taken seriously and to share a sexual sameness with God. Patriarchal socialization tells her that the elemental power of the female is somewhat shameful, dirty, and downright dangerous if unrestrained. Imagine, then, the ontological revolution that occurs within such a woman who immerses herself in sacred space where various manifestations of the Goddess bring forth the Earthbody from the spinning void, bestow fertility on field and womb, ease ripe bodies in childbirth, nurture the arts, protect the home, guard one's child against the forces of harm issue guidance for a community, join in ecstatic dance and celebration in sacred groves, and set love's mysteries in play. The woman's possibilities are evoked with a joyous intensity. She will create the ongoing completion of each mythic fragment. She is in and of the Goddess. She will embody the myth with her own totemic being. She is the cosmic form of waxing, fullness, waning: innocent virgin, mature creator, wise crone. She cannot be negated ever again. Her roots are too deep – and they are everywhere. (xiii – xiv)

While patriarchal religions consistently depict women as evil (e.g.: Pandora's box, Eve and the Tree of Knowledge, etc) or otherwise lesser than men and existing only to serve them, the Goddess upholds women and unites and celebrates them and their bodies. It's certainly a pleasant sentiment… but I'm just a cynic by nature, I think. Finding hope and happiness in religion is certainly much better than falling into a Nihilistic depression, but also I think it's important to keep a firm grasp on reality – like, positive affirmations and connecting with nature and the community are one thing, but pseudoscience and other forms of misinformation is another, y'know?

That's my biggest issue with the Goddess spirituality movement, honestly; it's essentially built on the idea of what Eller calls a “sacred history," where the earliest matriarchal religions and societies around Greece and other parts of the Mediterranean and Middle East, which allegedly existed around 5000 years ago or even older still, were wiped out and denigrated by later violent patriarchal societies, leaving almost no historical record. Every individual spiritual feminist seems to have her own interpretation of how this may have occurred and what those mythical early civilizations may have been like, often extrapolating small or even non-sensical details to be signs of Goddess worship at archeological sites, ranging from female figurines, wavy lines, various animals, and even phalluses (Eller 160).

Eller's later book, The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory (2000), goes on to explain how some feminist spiritualists don't even necessarily believe in this “sacred history," like author Donna Wilshire who said:

metaphoric truth which speaks to such a deep core of our common humanity and the meaning of life is more real than factual reality. (13)

Again, they apparently hold so tightly onto this myth because it gives them hope where otherwise they have nothing – in radical feminist ideology, patriarchy is all-encompassing, forever present and impossible to fight, but even just the idea that there was a time before male-dominated society makes it easier for these women to imagine a time after (18).

Eller also criticizes other pseudoscientific beliefs inherent to feminist spirituality, like bioessentialism. In the quote above from Spretnak, for example, it seems that she is still saying that women's purpose is to have children, that women are inherently nurturers, etc. Some of these women try to shift the focus to other things, like menstruation or creation in general (whether paintings, music, etc), but ultimately, they seem to come back to childbirth as a symbol of the “inherent differences" between the sexes (Eller 57-8). Unfortunately, this also inevitably loops back into defeatism: if women are inherently like this and men are inherently like that, then there's no point in trying to change society for the better…

But, let's put the lid back on that can of worms and get back to what we're here to discuss: adaptations of Persephone's myth!

In her 1988 article “The Eleusinian Mysteries Of Demeter And Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth," Mara Lynn Keller talks about how, based off of this interest in pre-patriarchal societies, it became popular to try to compare what was known about different religions around the Mediterranean to “reconstruct" the “original" versions of the stories (28). This is basically what Spretnak is aiming to do in her book, Lost Goddesses of Early Greece (first published in 1978). For example, she saw deep connections between Persephone and Isis of Egypt, the Goddess of the Underworld who could pass back and forth freely, and, after “becom[ing] that Goddess as much as possible," she came up with this: [1]

Demeter and Persephone share the bountiful fields, enjoying the beautiful earth, and watching over the crops together. One day, Persephone asks her mother about the restless spirits of the dead she has seen hovering about their earthly homes. "Is there no one in the underworld to receive the newly dead?" she asks. Demeter explains that she rules over the underworld as well as the upper world, but her more important work is above ground, feeding the living. Reflecting on the bewilderment and pain she has seen in the ghostly spirits, Persephone replies, "The dead need us, Mother. I will go to them." After trying to persuade Persephone to stay with her, Demeter relents: "Very well ... We cannot give only to ourselves. I understand why you must go. Still, you are my daughter, and for every day you remain in the underworld, I will mourn your absence." (Keller 39)

You will notice that in this retelling, Hades doesn't seem to exist at all. Instead, Persephone chooses to go into the Underworld to help comfort and bring peace to the dead. Later on, Demeter still becomes upset and prevents crops from growing out of mourning for her daughter, like we see in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, but Persephone comes back up periodically, bound to the Underworld only by a sense of personal duty to help others (Keller 40). As a feminist retelling, I guess this makes sense – it genuinely is her choice to go the Underworld and help however she can. It still seems extremely sanitized and boring, though, especially compared to the original Hymn. The characters don't have much personality and only seem to worry about caring for others – and, again, it seems to promote an idealized, shallow image of “feminine strength" and other “feminine virtues," like putting another's needs and desires above your own, emblematic of the bioessentialism mentioned earlier.

Feminist author Diane Stein tells another version of the myth in The Women's Spirituality Book (1987), where Demeter encompasses the entire universe and all creation but eventually gets lonely and decides to make Persephone, parthenogenically, as well. One day, Persephone is exploring and happens to find the entrance to the Underworld, where she meets none other than Hecate, who is another aspect of the triple Goddess. Persephone is curious and wants to learn all she can from Hecate, but is urged to return to the Earth and relieve her mother's suffering. It's painful, but they finally come to an agreement: Persephone can go down and listen to Hecate's teachings, but only for part of the year, during which Demeter will be in agony, creating the seasons (Stein 39-41). This one has Persephone acting out of her own curiosity, which is a nice change compared to patriarchal religions, but is frankly still rather bland and boring.

In the acknowledgements of her book, Spretnak says she was particularly inspired by her young daughter's curiosity about Greek myths, but also wanted to protect her from their extreme misogyny. I don't see why you wouldn't want to tell your daughter about the Hymn, though, honestly.

In it, we see Demeter as a fairly well-rounded character, experiencing a wide range of emotions (ex: lashing out at Zeus for taking her daughter, condemning the mother of Demiphoon for not trusting her unconditionally, suffering a devasting bout of depression but eventually softening due to a stranger's joke, joy at reuniting with her daughter, etc). While she is obviously suffering in a patriarchal society, she is still an independent, prideful woman who stands up for herself and does what she has to, to make herself heard (even if it involves almost killing all of humanity in the process). She's a character who has many facets and who the reader can likely see themself in; like how in the previous chapter, we talked about some examples of authors projecting their own experiences of grief onto her, finding comfort in the realization that they aren't alone in their suffering. It even shows her, while in disguise on Earth, being lovingly accepted by a group of women who offer her shelter, food, and companionship in her time of need – you would really think such things would be right up a feminist's alley, right?

I still think it's much better to show women continuing on with their lives and fighting back, even in a horrifically misogynistic world, rather than simply pretending misogyny and other problems don't exist, or daydreaming about a mythical pre-patriarchal past. Like, I've used this example before, but, as we've seen in Iceland, spinning narratives about how misogyny no longer exists or trying to shield the children from it or whatever doesn't actually do anything to interrupt our inherently sexist world – it just lures women into a false sense of security and makes it more difficult for them to speak out about their concerns.

In fact, I believe that these 70's and 80's spiritual feminist narratives directly led into the modern popular revisionism we see regarding Hades and Persephone, even if that was the exact opposite intention of these authors…

Endnotes

This is just an excerpt. You can read the full reconstruction here, starting on page 7, if you were curious. This version is reprinted in a periodical from the Worldwide Rosicrucian Order, which is apparently a group that is particularly interested in ancient religions and practices, especially involving death, the afterlife, rebirth, etc… The whole issue is devoted to the Eleusinian Mysteries and the cult of Persephone. ➥

Works Cited

Eller, Cynthia. Living in the Lap of the Goddess. Beacon Press, 1995. Print.

Eller, Cynthia. The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory. Beacon Press, 2000. Print.

Keller, Mara Lynn. "The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth." Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Spring, 1988), pp. 27-54 (28 pages). Indiana University Press. Online.

Spretnak, Charlene. Lost Goddesses of Early Greece: A Collection of Pre-Hellenic Myths. 1992. Beacon Press. Print.

.jpg)